Kindergarteners of working mothers score higher

This article also appeared here.

Here’s another data point in the mommy wars. Kindergarten children of full-time and part-time working parents score higher in both math and reading than their peers with a stay-at-home parent. But children with only a single parent had lower average test scores than either two parent scenario. That’s according to the Digest of Education Statistics 2012 that was released on Dec. 31, 2013. (The data is in Table 135). I was surprised to see that not only were the kindergarten entry test scores in the fall stronger of the children with working parents, but also the Spring kindergarten test scores. For example, a kindergarten child with two working parents scored, on average, 37 points in the fall of 2010, two points more than a kindergartener with one working parent and one stay-at-home parent. Whether the second parent works full time or part time doesn’t matter. The scores are equally high. That two-point lead continued in the Spring of 2011, when children of two working parents scored 52 points versus 50 points. The math gap was identical. Children with two working parents scored two points higher in both the fall and the spring than children with a stay-at-home parent.

What to make of this? I suspect the socio-economic profile of the stay-at-home mom has changed a lot in the past 20 years and that stay-at-home mothers might be, on average, less educated and less ambitious than their working counterparts. Perhaps the highly educated stay-at-home mother of the 1980s and 1990s is more likely to be a part-time worker today.

Top 10 education data stories of 2013

For my year-end post I’m highlighting my 10 favorite Education By The Numbers stories of the year. Thank you to everyone who has read and commented and made the first few months of this blog an interesting experiment. I look forward to continuing this conversation about education data with you in 2014.

1. Top US students lag far behind top students around the world in 2012 PISA test results

When you want to know why so many top PhD programs in the United States are filled with international students, perhaps one answer is that top U.S. students are rather mediocre testers when compared with their international peers. Not only are top US students ranked poorly, they’re doing worse on tests today than they did a decade ago.

This problem among the nation’s strongest students is confirmed in #8 top story below.

2. The number of high-poverty schools increases by about 60 percent

If you’re concerned about the growing disparity of wealth in the United States and wondering if it’s becoming increasingly difficult to escape poverty, this statistic about highly concentrated poverty in US schools might make you even more depressed.

3. Can an algorithm ID high-school dropouts in first grade?

4. California student-teacher ratio highest in the country

http://educationbythenumbers.org/content/california-student-teacher-ratio-highest-country_572/

5. Data analysis discredits widely used TERC math curriculum

6. Q&A with Knewton’s David Kuntz: ‘Better and faster’ learning than a traditional class?

On using data to tailor instruction to students.

7. Privacy, big data and education: more about the inBloom databases

My attempt, early in the inBloom data warehousing controversy, to understand student data privacy and how it could be breeched. Since then, States and districts pull back from InBloom Data warehouse

Are Hispanic students the driving force behind the rise in urban test scores?

When the National Center for Education Statistics reported on Dec. 18th that fourth and eighth graders in the country’s largest cities had shown marked improvement in test scores over the past decade, a question kept popping into my head. To what extent is white gentrification of cities driving this test score increase? Is it possible that the achievement gap between low-income inner-city minorities and the rest of America isn’t really closing by 30-40 percent, but a different population of youngsters with Ivy League-educated and artistic parents is now taking these tests?

Answering this question is proving tough. But here’s what I do see in the data tables.

1) High income kids of all races posted larger gains than low income kids in large cities between 2003 and 2013.

| Student Demographics |

Large City 2003 score |

Large City 2013 score |

Change |

| White Not Poor |

249 |

262 |

13 |

| Black Not Poor |

222 |

236 |

14 |

| Hispanic Not Poor |

228 |

244 |

16 |

| Asian Not Poor |

256 |

268 |

12 |

| All races Not Poor |

240 |

255 |

15 |

| White Poor |

231 |

238 |

7 |

| Black Poor |

210 |

221 |

11 |

| Hispanic Poor |

217 |

227 |

10 |

| Asian Poor |

238 |

248 |

10 |

| All races Poor |

217 |

228 |

11 |

Data source: NCES TUDA data 2013 for fourth grade math scores in large city public schools. Poor are students who are eligible for free or reduced priced lunch. “Not poor” are students who are not eligible for the lunch program. Data found using custom data tables here.

2) But to my surprise, the student population of large cities hasn’t shifted to become richer and whiter. Indeed, there are proportionally fewer whites in cities today and more poor kids than there were 10 years ago. The biggest changes are the decline in black populations and the rise of Hispanic populations.

| Demographics | % of fourth grade students in large cities2003 | % of fourth grade students in large cities2013 | Percentage Point Change |

| white |

22 |

20 |

-2 |

| black |

34 |

26 |

-8 |

| Hispanic |

36 |

43 |

7 |

| Asian |

7 |

8 |

1 |

| not poor |

27 |

26 |

-1 |

| poor |

69 |

73 |

4 |

Data source: NCES TUDA data 2013 for fourth grade math scores in large city public schools. Poor are students who are eligible for free or reduced priced lunch. Not poor are students who are not eligible. Data retrieved using custom data tables here.

(When you look city by city, however, you sometimes see a different picture. In New York City, for example, the percentage of white fourth graders has increased by 2 percentage points over the last decade to 17 percent. And the percentage of poor kids has declined 9 percentage points from 88 percent to 79 percent. So New York is richer and whiter. But the city had a modest 10 point increase in fourth grade math test scores.

(Washington DC, which had an impressive 24 point gain in fourth grade math test scores, had a much larger shift in its white population — up 9 percentage points to 13 percent. But student poverty also increased in the District by 5 percentage points to 76 percent.)

3) Next I tried to break down the demographic shifts by income. I was able to find NAEP TUDA data that broke down lunch program eligibility by race/ethnicity. I multiplied that figure by the share of students who were eligible (or not eligible). For example, 10% of all the city kids eligible for the lunch program in 2013 were white, and 73% of city kids were eligible for the lunch program. So .10 x .73 = 7% in the chart below. In other words, 7 percent of all urban fourth graders were white and poor.

| 2003% of large city student population | 2013% of large city student population | Change between 2003 and 2013 | |

| Not poor all races | 27% | 26% | -1 pct pt |

| White | 13% | 13% | 0 |

| Black | 5% | 3% | -2 pct pt |

| Hispanic | 6% | 5% | -1 pct pt |

| Asian | 3% | 3% | 0 |

| Poor all races | 69% | 73% | + 4 pct pt |

| White | 8% | 7% | -1 pct pt |

| Black | 28% | 22% | -6 pct pt |

| Hispanic | 29% | 37% | +8 pct pt |

| Asian | 4% | 4% | 0 |

Data source: NCES TUDA data 2013 for fourth grade math scores in large city public schools. Poor are students who are eligible for free or reduced priced lunch. Not poor are students who are not eligible. Data retrieved using custom data tables here.

Conclusion:

From this analysis, white gentrification doesn’t seem to be a driving force in the higher city scores. The percentage of whites who aren’t poor didn’t increase in the past decade. The bigger demographic shifts are the decline in the black population — both middle class and poor — and an increase in the Hispanic population.

I wish I had a finer way to measure income. There could be a churning of population within demographic categories. For example, middle class whites could have been replaced with wealthy whites. But since neither category qualifies for free lunch, this data wouldn’t capture that type of demographic shift.

Related stories:

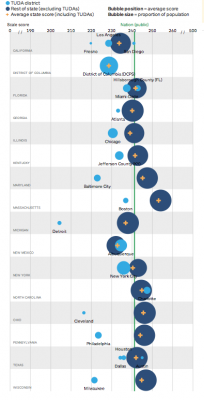

Top performing cities on NAEP test have the least poverty — but some poor cities do surprisingly well

This article also appeared here.

Do cities with less poverty test better? Yes, but the correlation is not as tight as you might guess, according to 2013 test scores released Dec. 18, 2013. I put together a spreadsheet looking at the percentage of students who qualify for free and reduced priced lunch in each of the 21 urban school districts that volunteered to be part of a National Center for Education Statistics assessment (known as NAEP TUDA). I then compared these poverty rankings to each city’s standing in fourth grade math. My original data came from here and here.

Charlotte, NC with the smallest percentage of poverty on the list (only 56%) has the top math score — as you might expect. But it’s interesting that Jefferson County, KY, which has the 4th smallest percentage of poverty (65% low income students) ranked 11th in math. You would have expected it to post a higher math score. Similarly, Atlanta and Washington DC post lower math scores than their poverty rankings would suggest. Conversely, Boston has higher poverty than most of the other cities. Yet its fourth graders posted the 5th highest score in math.

Here is my table….

| City | 4th Grade Math | 4th Grade Math Ranking | % Poverty | Least Poverty Ranking(Most poverty = 21) |

| Charlotte | 247 | 1 | 56 | 1 |

| Hillsborough County, FL | 243 | 3 | 58 | 2 |

| Austin | 245 | 2 | 62 | 3 |

| Jefferson County KY | 234 | 11 | 65 | 4 |

| San Diego | 241 | 4 | 66 | 5 |

| Atlanta | 233 | 12 | 73 | 6 |

| Miami-Dade | 237 | 6 | 74 | 7 |

| Washington DC | 229 | 14 | 76 | 8 |

| Albuquerque | 235 | 9 | 77 | 9 |

| New York City | 236 | 8 | 79 | 10 |

| Houston | 236 | 7 | 83 | 11 |

| Milwaukee | 221 | 18 | 83 | 12 |

| Chicago | 231 | 13 | 84 | 13 |

| Los Angeles | 228 | 15 | 84 | 14 |

| Boston | 237 | 5 | 85 | 15 |

| Baltimore | 223 | 17 | 87 | 16 |

| Detroit | 204 | 21 | 88 | 17 |

| Fresno | 220 | 19 | 91 | 18 |

| Dallas | 234 | 10 | 94 | 19 |

| Philadelphia | 223 | 16 | 94 | 20 |

| Cleveland | 216 | 20 | 100 | 21 |

Related stories:

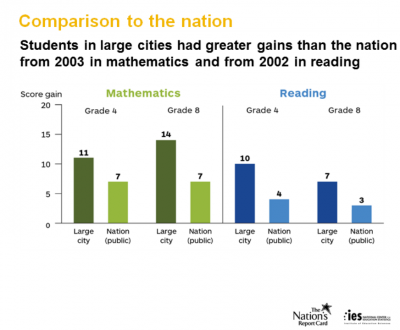

Low-income inner-city achievement gap starts to close, test scores of urban school districts improve faster than nation over past 10 years, Washington D.C. stands out

The test scores of fourth and eighth graders in large cities have been improving faster than the national average has over the past decade, according to federal test data released Dec. 18, 2013. Wide achievement gaps between large cities, often with huge concentrations of low-income minorities, and the average U.S. student have closed by as much as 43 percent.

“If you look solely at any two-year testing cycle, the results are sometimes less conclusive and they sometimes lead observers to conclude that urban schools are not making any progress. But if you stand back from the individual trees, you will see a forest that is growing taller and getting stronger,” said Michael Casserly, executive director of the Council of the Great City Schools, which works with the National Center of Education Statistics (a division of the US Department of Education) to collect samples of urban test scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, the main test that is taken throughout the country every year among fourth and eighth graders.

“In general, we are encouraged by the new results, but we are not satisfied with them. We know we need to accelerate. And we know that our gaps are still too wide,” Casserly added.

This year marks the first time that 10 years of urban test data is available in math and reading, enabling researchers to make conclusions about long-term trends. Cities above 250,000 people and with large concentrations of minorities and low-income students are invited to participate in this Trial Urban District Assessment (TUDA). In 2013, 21 of 36 urban districts that met these thresholds did. But 10 year trend data for math and reading is available only for the 10 districts that began participating back in 2002 and 2003. Test data covers public school students and excludes private schools. Charter schools are also largely excluded, especially those chartered by a state, but some cities maintain oversight of charter schools and may have included them. You can find all the data here.

Washington DC, which lags the nation in both math and reading, showed huge gains among fourth and eighth graders in both subjects since 2003 and 2011. It was the only city in the nation to show gains on all four tests since 2011. In fourth grade math, for example, Washington DC improved by 24 points since 2003, more than three times the national gain of 7 points during the same time period.

It is unclear what is behind the outsized gains in Washington DC. Gentrification and policy changes have happened simultaneously. Both white and Hispanic populations have grown considerably while the black population has fallen. For example, 3 percent of 4th graders were white back in 2003. In 2013, 13 percent were white. And within the declining black population, many higher income blacks have departed the district, leaving the black population within the District slightly poorer on average.

Still, urban districts, including Washington D.C., continue to lag behind the nation and the average of their home states. This bubble chart depicting fourth grade math scores shows how far behind most of these 21 cities are. Each blue dot represents a city. And you can see how the blue dots trail the big navy dots (their home states) and the green line (the nation). The exceptions are Charlotte, Austin, Hillsborough County (FL) and San Diego, all of whose poverty rates are lower than typical big cities. On the other end of the spectrum, nearly 100 percent of the students in the Cleveland public schools qualify for free and reduced price lunches, the measure of poverty used in this data collection. Click on the chart itself to see it pop up in a larger size. You can generate your own version of this chart on the NCES website.

A list of the 21 cities that participate in the Trial Urban District Assessments.

1. Albuquerque Public Schools

2. Dallas Independent School District

3. Hillsborough County (Tampa, Fla.)

4. Atlanta Public Schools

5. Austin Independent School District

6. Baltimore City Public Schools

7. Boston Public Schools

8. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools

9. Chicago Public Schools

10. Cleveland Metropolitan School District

11. Detroit Public Schools

12. District of Columbia Public Schools

13. Fresno United School District

14. Houston Independent School District

15. Jefferson County Public Schools (Louisville, Ky.)

16. Los Angeles Unified School District

17. Miami-Dade County Public Schools

18. Milwaukee Public Schools

19. New York City Department of Education

20. San Diego Unified School District

21. School District of Philadelphia

Teacher and school workplace injuries decline in 2012, but violent injuries increase

Teaching is not a particularly dangerous or injury-prone occupation, especially when compared with, say, nursing, policing or driving. But it is still interesting to see just how many workplace injuries teachers do suffer in the Bureau of Labor Statistics annual report on the nation’s workplace injuries. And people employed in education in public schools seem to be have had a safer work environment in 2012 than in 2011.

In 2012, a little more than 56,000 people employed in local government education services suffered an injury on the job, an incidence rate of 108 injuries per 10,000 workers. That’s down from 2011 when 63,950 injuries were reported in public schools, an incidence rate of 120.5 injuries per 10,000 workers. The days taken off from work is going up however. The median days missed for a workplace injury for local government education services was 8 in 2012, a day more than in 2011.

But what caught my attention was a subcategory of injuries caused by violence by another person or animal. That incidence rate increased in 2012 for people working in public schools to 13.9 violent injuries on the job for every 10,000 workers from a 12.3 incidence rate in 2011.

I’m not exactly clear what kinds of jobs fall under local government education services. I believe they include not only teachers, but also janitors and school security guards.

People employed in private sector educational services had about half the rate of total injuries (55.5 injuries per 10,000) and violent injuries (6.8 injuries per 10,000) of their public school counterparts.

On the final page of the annual report, elementary school teachers are broken out as a separate category in an analysis of musculoskeletal on-the-job injuries. More than a thousand Elementary school teachers across the nation suffered these kind of injuries in 2012, down from roughly 1500 in 2011. The incidence rate (injuries per 10,000 workers) declined to 9.9 from 13.2. But just as before, the median number of days being taken off from work for each injury is increasing — seven days in 2012 instead of five in 2011.

The public school injury rate for elementary school teachers was double the rate for private schools.

Here are links to the 2012 and 2011 data reports, each released in the November of the following year.

PISA math score debate among education experts centers on poverty and teaching

I’ve been enjoying the posts on how to interpret the PISA math scores. Everyone agrees that average math performance among American 15 year olds is disappointing with the US ranking 36th among 65 nations and subregions.

Michael Petrilli wrote a piece, PISA and Occam’s Razor, arguing that poverty might not the reason the US fares so poorly and thinks, perhaps, there’s a problem with teaching. “Maybe we’re just not very good at teaching math, especially in high school.”

There’s been an emotional, impassioned rebuttal, arguing that poverty is what is dragging the US down and we would otherwise be excellent. Do not blame the teachers.

On Diane Ravitch’s blog Daniel Wydo Disaggregates PISA Scores by Income makes the case that poverty is to blame by isolating rich schools in the US. If you looked at only schools in which fewer than 10% of the population is poor, the US would rank #1 in reading, #1 in science and #5 in math.

Bruce Baker’s School Finance 101 blog takes on Petrilli’s in this post, showing clearly that poverty affects math scores.

Of course poverty matters. The US has a real problem educating poor children. The gaps are clearly worse in high school than in elementary school. The rich-poor gap in the United States is bigger than the rich-poor gap in many other countries. But we also have a real problem with our top students.

The flaw in the Wydo analysis is that it’s silly compare students from the richest schools in America with the entire mass of another country. The PISA report clearly states that there are more variations within countries than between countries. (In Lichtenstein, a top performing country, roughly 250 points separate top and bottom students. That’s more than the point difference between top ranked Shanghai and bottom ranked Peru). Every country’s mean score is weighed down by its poor students and its unfair to compare your best students with the average student elsewhere. The fair comparison would be to compare rich schools in the United States with rich schools in Switzerland and the Netherlands. And I think you would find (I don’t immediately see the income data on the PISA website to do this number crunching) that the US would NOT compare favorably.

I think this because PISA serves up data on the 90th percentile in each nation and top American students are also below average. So poverty alone cannot explain mediocre math performance.

My conclusion is that it’s not an either or. Perhaps the US has two separate problems. One is poverty. Two is high school math education.

Related story:

Top US students lag far behind top students around the world in 2012 PISA test results

Interview: Jill Barshay on PISA scores, backsliding of top US students, Asian testing strength

Hechinger Report contributing editor Jill Barshay took part in a podcast, “The United States Gets a C,” with American Radio Works this week (Dec 10, 2013).

“The results are in from academic tests of 15-year-olds in 65 countries and regions. PISA shows Finland slipping, Vietnam doing well, and the United States still middle of the pack.”

Barshay and host Stephen Smith discussed these topics:

1) How are top US students faring internationally?

2) Finland’s slide, Vietnam’s debut

3) Why are Asian educational systems so strong?

Top US students lag far behind top students around the world in 2012 PISA test results

Top U.S. students, those that are among the top 10 percent of the population, lag far behind the top students in the highest achieving countries, a gap that is far bigger than the gap between the bottom students in the United States and elsewhere. That’s if you measure it by the results of the 2012 PISA test, given to 15 year olds across the world.

I wanted to dig deeper into the 2012 PISA test results, released Dec. 3, 2013, to see not just how the average American 15-year-old performs, but how both extremes are faring. First, I isolated the top 10 percent of students (aka 90th percentile) in each of the 65 countries or subregions tested by the OECD and ranked their math scores. The top 10 percent here earned a score of 600, on average, putting the US in 34th place. That’s about the same ranking as the average US student, whose score of 481 places 36th among nations. But the score gaps at the top are bigger than I expected. Top US students are more than a 100 points below the top students in Shanghai Singapore and Taipei. That’s the equivalent of several years of schooling. By contrast, the bottom 10 percent of US students lag the bottom students of the top achieving regions by much less than 100 points (except for in Shanghai, where the bottom 10 percent of students approach the score of the average American 15 year old!)

I’d also like to emphasize that scores of the top 10 percent in the United States have been declining over the past decade. See this post.

Here follow charts for the top 10 percent, the bottom 10 percent. I took spreadsheets from the PISA report annex, filtered for 90th and 10th percentile scores, ranked them and deleted everything else. For reference, here’s a link to the global rankings, that list the average scores for each nation. See Table 1A, page 19.

2012 PISA Math Scores for the Top 10 Percent (90th Percentile)

| Ranking | Country or Subregion | 90th Percentile Score |

| 1 | Shanghai-China | 737 |

| 2 | Singapore | 707 |

| 3 | Chinese Taipei | 703 |

| 4 | Hong Kong-China | 679 |

| 5 | Korea | 679 |

| 6 | Macao-China | 657 |

| 7 | Japan | 657 |

| 8 | Liechtenstein | 656 |

| 9 | Switzerland | 651 |

| 10 | Belgium | 646 |

| 11 | Netherlands | 638 |

| 12 | Germany | 637 |

| 13 | Poland | 636 |

| 14 | Canada | 633 |

| 15 | New Zealand | 632 |

| 16 | Australia | 630 |

| 17 | Finland | 629 |

| 18 | Estonia | 626 |

| 19 | Slovenia | 624 |

| 20 | Austria | 624 |

| 21 | France | 621 |

| 22 | Czech Republic | 621 |

| 23 | United Kingdom | 616 |

| 24 | Luxembourg | 613 |

| 25 | Slovak Republic | 613 |

| 26 | Iceland | 612 |

| 27 | Portugal | 610 |

| 28 | Ireland | 610 |

| 29 | Denmark | 607 |

| 30 | Italy | 607 |

| 31 | Norway | 604 |

| 32 | Israel | 603 |

| 33 | Hungary | 603 |

| 34 | United States | 600 |

| 35 | Spain | 597 |

| 36 | Latvia | 597 |

| 37 | Lithuania | 596 |

| 38 | Sweden | 596 |

| 39 | Russian Federation | 595 |

| 40 | Croatia | 589 |

| 41 | Dubai (UAE) | 587 |

| 42 | Turkey | 577 |

| 43 | Serbia | 567 |

| 44 | Greece | 567 |

| 45 | Bulgaria | 565 |

| 46 | Romania | 553 |

| 47 | United Arab Emirates – Ex. Dubai | 538 |

| 48 | Thailand | 535 |

| 49 | Chile | 532 |

| 50 | Malaysia | 530 |

| 51 | Kazakhstan | 527 |

| 52 | Uruguay | 526 |

| 53 | Montenegro | 520 |

| 54 | Qatar | 514 |

| 55 | Mexico | 510 |

| 56 | Albania | 510 |

| 57 | Costa Rica | 496 |

| 58 | Brazil | 495 |

| 59 | Tunisia | 488 |

| 60 | Argentina | 488 |

| 61 | Jordan | 485 |

| 62 | Peru | 478 |

| 63 | Colombia | 474 |

| 64 | Indonesia | 469 |

| Annex B1 | ||

| Version 1 – Last updated: 26-Nov-2013 | ||

| Table I.2.3d | ||

| Distribution of scores in mathematics in PISA 2003 through 2012, by percentiles | ||

2012 PISA Math Scores for the Bottom 10 Percent (10th Percentile)

| Rankings | Country or Subregion | 10th Percentile Score |

| 1 | Shanghai-China | 475 |

| 2 | Singapore | 432 |

| 3 | Chinese Taipei | 402 |

| 4 | Hong Kong-China | 430 |

| 5 | Korea | 425 |

| 6 | Macao-China | 415 |

| 7 | Japan | 415 |

| 8 | Liechtenstein | 403 |

| 9 | Switzerland | 408 |

| 10 | Belgium | 378 |

| 11 | Netherlands | 397 |

| 12 | Germany | 385 |

| 13 | Poland | 402 |

| 14 | Canada | 402 |

| 15 | New Zealand | 371 |

| 16 | Australia | 382 |

| 17 | Finland | 409 |

| 18 | Estonia | 417 |

| 19 | Slovenia | 384 |

| 20 | Austria | 384 |

| 21 | France | 365 |

| 22 | Czech Republic | 377 |

| 23 | United Kingdom | 371 |

| 24 | Luxembourg | 363 |

| 25 | Slovak Republic | 352 |

| 26 | Iceland | 372 |

| 27 | Portugal | 363 |

| 28 | Ireland | 391 |

| 29 | Denmark | 393 |

| 30 | Italy | 366 |

| 31 | Norway | 373 |

| 32 | Israel | 328 |

| 33 | Hungary | 358 |

| 34 | United States | 368 |

| 35 | Spain | 370 |

| 36 | Latvia | 387 |

| 37 | Lithuania | 364 |

| 38 | Sweden | 360 |

| 39 | Russian Federation | 371 |

| 40 | Croatia | 360 |

| 41 | Dubai (UAE) | 342 |

| 42 | Turkey | 339 |

| 43 | Serbia | 335 |

| 44 | Greece | 338 |

| 45 | Bulgaria | 320 |

| 46 | Romania | 344 |

| 47 | United Arab Emirates – Ex. Dubai | 318 |

| 48 | Thailand | 328 |

| 49 | Chile | 323 |

| 50 | Malaysia | 319 |

| 51 | Kazakhstan | 343 |

| 52 | Uruguay | 297 |

| 53 | Montenegro | 306 |

| 54 | Qatar | 257 |

| 55 | Mexico | 320 |

| 56 | Albania | 278 |

| 57 | Costa Rica | 323 |

| 58 | Brazil | 298 |

| 59 | Tunisia | 292 |

| 60 | Argentina | 292 |

| 61 | Jordan | 290 |

| 62 | Peru | 264 |

| 63 | Colombia | 285 |

| 64 | Indonesia | 288 |

| Annex B1 | ||

| Version 1 – Last updated: 26-Nov-2013 | ||

| Table I.2.3d | ||

Related stories:

Top US students decline, bottom students improve on international PISA math test

U.S. private school students not much better than public school students in math

Top US students decline, bottom students improve on international PISA math test

| Distribution of scores in mathematics in PISA 2003 through 2012, by percentiles | ||||||||

| PISA 2012 | Change in percentiles between 2003 and 2012 (PISA 2012 – PISA 2003) |

|||||||

| Percentiles | 10th | 25th | 75th | 90th | 10th | 25th | 75th | 90th |

| Score | Score | Score | Score | Score dif. | Score dif. | Score dif. | Score dif. | |

| United States | 368 | 418 | 543 | 600 | 11 | 0 | -6 | -7 |

Source: OECD, PISA 2012, Annex B1 (Table I.2.3d)

Overall, the test score of the average US 15-year-old student hasn’t changed much in the past decade. PISA math scores for 2012 were 481, not that different from the 483 posted in 2003.

But that masks movement among different student groups. It turns out that the weakest 10 percent of US students have been steadily improving, gaining 11 points over the past decade. Meanwhile, the top two tiers of American students at the top 10th and top 25th of the nation are performing worse today than they did a decade ago, losing 7 points and 6 points respectively.

So I stand corrected from an earlier post where I wondered if US students were simply stagnating while students in other nations, especially in Asia, are learning more and improving year after year. Top US students are not only being outrun by their Asian peers, they’re sliding backwards.

I wonder if the pressure on US teachers to bring as many students as possible up to some sort of arbitrary “proficient” level on state assessments is exacerbating the problem at the top. In order to maximize the number of students that can hit a minimum threshold, instruction inevitable gets directed down toward the students who are just below average to help prop them up. Meanwhile, advanced students are being asked to repeat the basics over and over again and aren’t being pushed. It’s another argument for measuring learning gains or educational growth among all students and not how many kids can hit a certain threshold.

These PISA results, broken down by percentile, have me scratching my head a bit. Earlier national test data from NAEP showed that top students were improving more than bottom students. There were many examples of the bottom students slipping.

Related stories:

Low income students show smaller gains within Washington DC’s NAEP test score surge