More than a decade ago a company called Renaissance Learning developed a computerized way for teachers to track students’ reading outside of the classroom. Instead of pasting stars on a chart each time a student says he has read a book, the teacher sits a student in front of a computer screen to answer a quiz on the book to prove he’s read it. The computer keeps track of how many and which books a student has read, along with the level of reading difficulty and whether a student has understood the basics of the story.

The program isn’t perfect; some students complain, for example, that a book they want to read from the library isn’t in Renaissance’s catalog of 165,000 book quizzes, and so it can’t be counted. But there are now almost 10 million students in the United States using the program, called Accelerated Reader, in more than 30,000 schools. It might be the biggest survey of reading in the country. This year, the director of educational research at Renaissance learning, Eric Stickney, mined the data, not just to see which books are the most popular*, but to gain insight into how kids become better readers as they progress from first grade through 12th. The company released the data from the 2013-14 school year — anonymized and aggregated to protect student privacy — on Nov. 18, 2014, and plans to make it an annual report. (Click on the “Why It Matters” tab to access the report).

This article also appeared here.

Caveats about the data: It’s not a nationally representative sample. More than a third of the children are from rural schools, whereas nationally, less than one fifth of students are in rural schools. So the tastes and habits of rural children are overstated. Otherwise, income and racial characteristics of the students come fairly close to the nation’s. Almost half of the students included in the data are poor, qualifying for free or reduced price lunch.

Here are three findings:

1. Girls read 800,000 more words

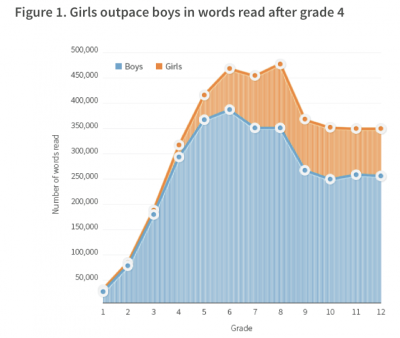

Girls read more books than boys do, in every grade, but boys aren’t that far behind girls from kindergarten through third grade. It’s beginning in fourth grade that reading habits really diverge by gender.

Starting in fourth grade, girls read, on average, 100,000 more words per year than boys do. Over the course of a child’s elementary, middle and high school education, that adds up to an almost 800,000-word difference (3.8 million words for girls vs. 3 million words for boys). The chart above shows the number of words that boys and girls, on average, read in each grade.

“It’s striking,” said Stickney, the research director at Renaissance. “It’s hard to learn new words when you’re not exposed to them, and girls are getting exposed to a lot more words.”

Stickney sees a strong connection between how much girls read and their higher scores on standardized reading tests. It might not be that girls are naturally better at reading, but that they simply do more of it, so they get better at learning vocabulary, for example, which is a big part of standardized reading assessments.

Thinking about the quantity of words absorbed reminds me of Betty Hart and Todd R. Risley’s early-childhood studies, which found that the more that parents or caregivers talked to a child from birth to age 3, the better off the child would be in school. These psychologists concluded that many low income children start school at a deficit because they haven’t heard as many words as high income children have. Perhaps the persistent female-male achievement gap on reading tests can be explained by these read (or unread) 800,000 words.

2. “The sweet spot” is 15 minutes a day

The good news is that the data also show that the more anyone reads, the more his or her reading ability improves over the course of a school year.

“Struggling students who read a lot have strong gains,” said Stickney.

A student who began the year in the bottom 25 percent of readers but proceeded to read for a half-hour a day and successfully answered quizzes on the books caught up with his class by the end of the year. In numerical terms, he jumped from 12th percentile to 48th percentile in one year. Admittedly, not a lot of students in this bottom category had this motivation — fewer than 25,000 students from the cohort of 10 million. But their growth was so strong, it outpaced the growth of advanced students who read just as much.

To be sure, mindlessly reading book after book doesn’t make you a scholar. Stickney found that comprehension was the key to the learning gains. For example, a child who read 30 minutes a day but answered fewer than 65 percent of the quiz questions correctly didn’t show strong improvement over the year. Indeed, this type of high-volume reader didn’t do any better than lazier students who didn’t bother reading much.

But a student who read between 15 and 30 minutes a day and answered 85 percent or more of the comprehension questions correctly scored 80 percent higher than his peers on a reading assessment in the spring. There wasn’t much additional benefit from exceeding a half hour of reading — only 3 more percentile points in achievement gains. The report calculates that 15 minutes of engaged reading time per day is “the sweet spot” for reading growth, after which students still benefit, but there are diminishing returns. Engaged time is not the same as clock time. The report estimates that a parent or teacher needs to schedule 35 minutes on the clock to achieve 25 minutes of engaged reading time.

The opportunity for a struggling student to surge ahead remained true for all the grades Stickney studied, from first through 12th. But Stickney did see larger gains from hard work in the earlier grades than in the older grades. For example, an elementary school student who read for a half-hour every day (and answered quiz questions correctly) tended to post a reading achievement growth rate that was 86 percent higher than that of his peers. The gains for these voracious readers fell to 70 percent in middle school and finally to 67 percent in high school. “Students, when they’re younger, tend to grow more in everything they do,” Stickney said. “The gains by year tend to be smaller as you get older.”

3. Supercharged learning

Which students showed higher rates of reading growth than everyone else? Stickney found accelerated growth for students who read challenging books that were above the students’ designated reading level. “These students really do grow,” he said. “They have even higher gains.”

But this supercharged growth occurred only when the student understood a majority of the book’s main points. The problem is that many students pick up a challenging book from time to time (about 12 percent of the 330 million books read on the Renaissance’s program were above the student’s designated reading level), but don’t comprehend it well. For these students, there was usually no benefit; they would have learned more had they embraced a book at their reading level.

So should a parent or teacher push a student to stretch and read a tough text? It depends. Stickney says it can’t hurt to give it a shot and see if the child can handle it. Some children are more inclined than others to look up a word in the dictionary. Perhaps a teacher can offer other comprehension strategies.

* If popularity lists are what interest you, you can use this search tool to see the top 10 books by grade, gender and state here.

Related: Three lessons from the science of how to teach writing and Right and wrong methods for teaching first graders who struggle with math