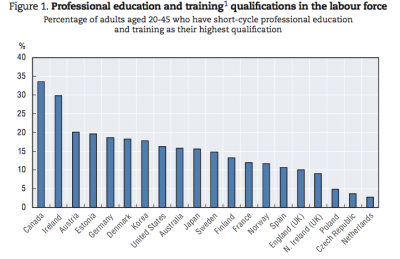

Source: OECD Skills Beyond School Synthesis Report Nov 2014. Click on the chart to see a larger version.

I had long been under the impression that the United States had a particular problem in providing technical and specialized professional training for students who maybe aren’t academically inclined. But it turns out the United States isn’t alone, and even nations with once vaunted apprenticeship programs are no longer properly training students to enter the workforce.

A new report finds that the vocational training programs in 20 economically developed countries aren’t producing enough students with the skills to be junior managers, health care technicians and other workers that the labor market needs. It says that two-thirds of all job growth in the European Union is forecast to be in the “technicians and associate professionals” category. In the United States, nearly one-third of job openings in 2018 will require some sort of professional training after high school, but not a four-year degree, according to the Nov. 13, 2014 report, “Skills Beyond School Synthesis Report,” by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

This article also appeared here.

Yet, in most countries, less than 20 percent of the labor force (aged 20 to 45) has a vocational certification. In the United States, only 12 percent of the labor force has a vocational certification. Another 10 percent has an associates degree; some of these degrees require applied career training, but many do not.

“Every county needs to upgrade,” said Stanley Litow, an IBM vice president who helped launch a new “P-Tech” model for vocational training in the United States. “Even the good apprenticeship programs are training for a narrow set of skills. Change is happening at a much faster pace. What we need are strong academics and workplace preparation that doesn’t prepare people for one job that doesn’t exist in the future.”

It’s interesting to consider this report in light of bleak employment prospects for some college graduates with four-year bachelor’s degrees. Many end up in low-paying jobs that don’t require expensive degrees. Perhaps some undergraduate students should consider obtaining a high quality technical certification instead. To be sure, many of the underemployed college students studied humanities and social sciences, such as sociology and psychology. Who knows if these students would enjoy a professional training program in, say, management.

The report documents how programs designed for the factory floor, such as manufacturing, engineering and construction, are falling out of favor across Europe and other developed nations. In Germany, enrollments in some specialties have fallen 50 percent. But a specialty known as “Fachwirt” — roughly akin to business administration, and commonly hired in health care and other service fields — has risen in popularity by 45 percent, and is now the most common advanced vocational exam taken. Still, vocational training is falling out of favor altogether among young Germans. The number of advanced vocational certification exams taken each year fell 24 percent from 1996 to 2010.

In the United States, health care is the most popular vocational field, accounting for 25 percent of the vocational degrees and certifications in the labor force, followed by engineering, manufacturing and construction. Teacher training is one of the least popular vocational subjects in North America and most of Europe, but it is very popular in Japan, Korea and Denmark. (Table 1.1 on page 31 of the report shows the breakdown for each country by speciality).

Data collection and analysis for vocational training is particularly difficult. Each country uses different labels and terminology. It’s a little-understood world of colleges, trade associations, diplomas, certificates and professional examinations without consistent standards. Vocational training is often lumped together with college or university education. Even to count the number of vocational degrees, researchers must tease out the numbers through statistical techniques and judgment calls. For example, some two-year degrees are more vocational in nature than others. U.S. students who complete vocational associates degrees make much more money than those who end their education with an academic associates degree, the report also notes.

The OECD authors argue that in order to enhance the image and status of vocational education, it should be uniformly renamed “professional education and training,” a term that is used in Switzerland.

But IBM’s Litow says that policy makers should focus more on revamping the content of vocational programs than on how they are labeled. “The problem is that vocational programs aren’t delivering,” he said. “We need to make large scale changes. I wouldn’t worry about what you call it.”

Litow hopes to expand his P-Tech model, which combines high school with two years of post-high school career training, including mentoring and internships, into nearly 100 schools by 2016. It began in 2011 as a pilot school in Brooklyn, N.Y., and is now in 27 schools across the country.

Related: Reflections on the underemployment of college graduates