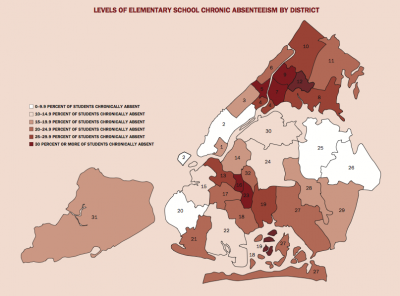

Map of New York City, showing neighborhoods with the highest rate of chronic absenteeism in the elementary schools. South Bronx and Central Brooklyn are shaded dark red. Center for New York City Affairs, The New School, November 2014 (Click on map to see a larger version)

How do you identify a bad elementary school?

A new report out of New York City suggests that policy makers should identify troubled schools by their absenteeism rates — a relatively easy data point to obtain — and then work to fix the schools by addressing each one’s unique problems, from homelessness and child abuse to teacher turnover and safety.

The report, “A Better Picture of Poverty: What Chronic Absenteeism and Risk Load Reveal About NYC’s Lowest-Income Elementary Schools,” released Nov. 6, 2014 by the Center for New York City Affairs at The New School, is part of a growing body of literature that argues that the poverty level of schools’ populations isn’t necessarily a good way to identify schools that need extra resources.

The study points out that 87,000 elementary school children, from kindergarteners to fifth-graders, missed more than 10 percent of the 2012-13 school year. Some schools were affected much more than others by this chronic absenteeism. The researchers found that, at 130 elementary schools, at least one-third of the students were chronically absent for five consecutive school years. It was even worse at 33 of these schools, where more than 40 percent of the student body missed more than 10 percent of the school year for five years straight. (In New York City, 10 percent of the 180-day school year is about 18 missed school days, almost a month of school).

This article also appeared here.

That affects not only the children who are missing school, but also the kids who are showing up. Teachers can’t move forward with new material when such a high percentage of children have missed earlier lessons and can’t keep up. The evidence is in the test scores: Only 11 percent of the students at schools with chronic absenteeism passed the city’s math and reading tests in 2012-13. Other schools with similar poverty levels but better attendance rates posted much higher test scores.

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio took a different approach when he announced a new initiative on Nov. 3 to help a group of failing schools. The schools on de Blasio’s list were selected because their test scores had been stubbornly low for several years straight. His $150 million program plans to bring community services, such as social workers, psychiatric help and health care, into schools in poor neighborhoods. The program also involves lengthening the hours of the school day and expanding the school year to weekends and summertime.

The New School’s report’s list of the 35 elementary schools with the worst attendance problems includes nine from the de Blasio list, but the New School’s list of needy elementary schools is longer. “Maybe not all of these are the bottom of the barrel,” said Kim Nauer, the lead author of the New School report. “But I would argue that they deserve community school funds.”

Nauer found that schools with chronic absenteeism were likely to be beset by other poverty-related problems, such as male unemployment in the neighborhood and high rates of homelessness. But there was no common set of risk factors that applied to all the schools with chronic absenteeism. Her team created a “risk load” assessment, noting how much 18 different risk factors are affecting every public elementary school in the city. She hopes that this will help school leaders and community groups identify the support that each school needs. You can search her data by school here.

The New School Center has been documenting chronic absenteeism in New York City’s schools since 2008, when almost 29 percent of the city’s students were chronically absent. That declined to under 25 percent in 2012-13.

One school that has succeeded in combating chronic absenteeism is P.S. 48, an elementary school in South Jamaica, a poor neighborhood in Queens. Back in 2012, 160 of the school’s 550 students had been chronically absent. Principal Patricia Mitchell slashed that to about 20 students in 2013. Her school’s passing rate on the city’s standardized test more than doubled. Previously a social worker, Mitchell said she had paid home visits to understand why students weren’t coming to school. She learned, for example, that some parents weren’t getting to the laundromat often enough and didn’t want to send their kids to school in dirty uniforms. So she bought a washer and a dryer for the school and has school aides doing the laundry. She also holds regular parties to celebrate improvements in students’ attendance, replete with pizza, music, Macy’s gift cards and outings to Dave & Buster’s video arcade. “It’s like they won the lotto,” Mitchell said.

But not all schools that have reduced absenteeism have seen academic improvements. According to Nauer, a group of schools in the South Bronx hasn’t seen an improvement in test scores despite achieving better attendance figures. In the case of the Queens elementary school, it might be other things that Mitchell has done to improve the school that are raising student performance. That same year that attendance soared, Mitchell also won a $1.2 million grant from an outside foundation to bring in 15 community groups to help students and provide after-school enrichment programs. Not many high-needs schools have savvy administrators with the time and energy to write a successful grant proposal like that.

“Chronic absenteeism — it’s the signal,” said Nauer. “Then you need to fix the schools. You need to do detective work to figure out what’s going on. Each school is different.”

Related stories:

Lessons from Hawaii: tracking the right data to fix absenteeism