Ed Data Geek David Stewart says tracking interim assessments isn’t useful.

In a Wired blog, “Inside the Educational Data Revolution,” David Stewart, CEO of Tembo, laments how in the largest US school systems, “millions of dollars are being spent on interim assessment systems, intended to track student performance throughout the year and adapt teaching strategies in advance of the high-stakes year-end tests. The problem is that there’s almost zero correlation between Common Core skills scores on the interim test and the end-of-year test. The difficulty levels are different, and the magnitudes of those discrepancies even differ among subject areas. Just because a student does well on a mid-year test doesn’t mean she will do well at the end of the year, making it impossible to track improvement. ”

I keep wishing that ed data geeks would use their data analytics to figure out which ways of teaching are more effective. But lower down in this blog post, there’s an explanation of why this may also be fool hardy.

“Steve Cartwright, the company’s Director of Analytics, “we really need to bring the individuals that are doing the teaching along for the ride.” Because, even to the data geeks at Tembo, it’s still ultimately about the classroom, where the rubber hits the road. “There are a lot of smart people all over the country trying to figure out the perfect lesson, the perfect way of instructing, and then replicating it for all students,” explains Stewart. But it’s more personal than that, and education is still struggling with escaping the one-size-fits-all approach. Given the widely differing starting points of each individual – learning style, home environment, motivation level – “you’re never going to solve it with an algorithm.”

Still, if we can do clinical studies for medicine in which each body processes a pill differently, why can’t we do it for teaching algebra?

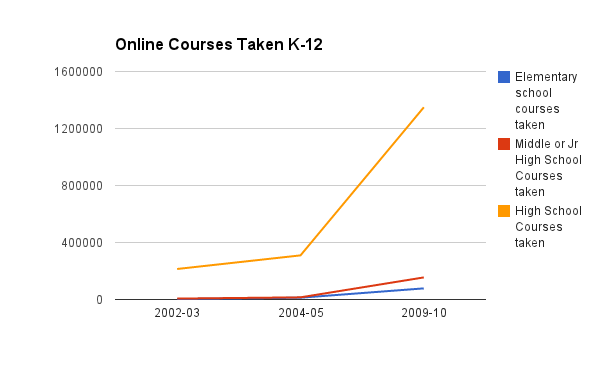

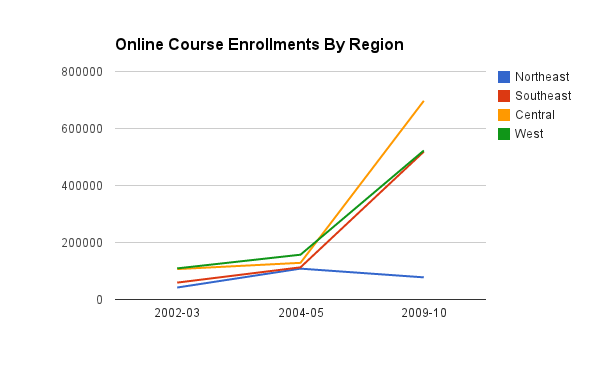

K-12 Online Education data show greatest growth in red states

I was looking for trends in the online education figures last compiled by the National Center of Education Statistics in November 2011 (Table 121 in the 2012 Digest of Education Statistics). The data we have count how many school districts offer online classes for K-12 students and how many online courses students are taking. There are only three years of data (2002-03, 2004-05 and 2009-10 academic years).

Not surprisingly, high schoolers are taking more online courses than elementary or middle school students. But in percentage terms, the greatest growth was in middle school, in which online enrollments grew more than 10 fold between 04 and 09.

But the geographic variations really popped out at me.

Why would the Northeast, the region of the country with the highest performing school systems, be turning its back on online courses? And why would the growth of online course taking be stronger in the Southeast and Midwest than the West Coast, where technology adoption is the strongest?

If you were to overlay a political map of the US onto this, you would see that red (Republican) states are more likely to be using online courses in K-12 education than blue (Democratic) states. One explanation is that teachers unions are stronger in blue states and are pushing back against the use of online courses in schools. Another explanation could be that education budgets are more constrained in red states. They’re more likely to seek out cheaper online courses than hire a teacher that can teach AP Physics.

I’m guessing that online courses will ultimately play a small role in traditional schools. But the use of software modules within a teacher-led classroom is likely to increase. Would love to see data tracking so-called “blended learning”.

New World Bank education data portal shows that Nigeria has weak early childhood programs

I was just tinkering around on the new education data portal, called Saber, launched by the World Bank in January 2014 that supposedly lets you compare education data across developing countries. I looked at Early Childhood Education programs. Data was available for only eight nations (Colombia, Kyrgyz Republic, Liberia, Nigeria, Samoa, Sierra Leone, Tajikistan and Tanzania). It was striking that Nigeria, the most populous country in Africa and soon to be the continent’s largest economy, has very weak early childhood education programs, according to the World Bank rating system. Even Tanzania, for example, is stronger.

I was thinking about Tiger Mom Amy Chua’s recent opinion piece, What Drives Success?, in the New York Times and how Nigerian immigrants do remarkably well in the United States.

“Nigerians make up less than 1 percent of the black population in the United States, yet in 2013 nearly one-quarter of the black students at Harvard Business School were of Nigerian ancestry; over a fourth of Nigerian-Americans have a graduate or professional degree, as compared with only about 11 percent of whites.”

So Nigerians don’t come from a culture that emphasizes early childhood education, but are nonetheless remarkably successful. I wonder if cultural values trump education?

Internet instruction favored more by wealthy than poor Americans

A fascinating opinion poll released January 29, 2014 by Harris Interactive and Everest College says that high-income Americans are more open to learning over the Internet than low-income Americans. Both groups prefer hands-on learning as their first choice (52% of Americans listed active participation through hands-on training as the best learning method). But the Internet came in second for high-income Americans. Thirty percent of American households earning more than $100,000 said they learn best over the Internet. Only 18% of Americans with household incomes below $35,000 said they learn best over the Internet.

What fascinates me is that computerized instruction is sometimes found to be more effective with low-income students (see this Raz-Kids app study) and many low-income charter schools are charging ahead with using iPads in the classroom (see this and this story). So the families that are most likely to be exposed to so-called digital learning might be the most skeptical about its efficacy. And maybe that explains why some low income families don’t encourage their children to use educational software at home. I wonder if the so-called digital divide is not just about low-income Americans not having access to high-speed Internet and computers, but there’s also a psychological resistance at play?

Related Stories:

Kindergarteners at the keyboard

In New Jersey, teachers union fights blended learning

Data show students who race through a typing app learn less, but possibly more in a reading app

New York City Independent Budget Office says per pupil spending is increasing

Per pupil funding in public schools dropped nationwide in 2011, but if New York is any indicator, it has since rebounded. A new chart, entitled, “New York City Public Schools: Have Per Pupil Budgets Changed Since 2010-2011?,” posted by the New York City Independent Budget Office on January 23, 2014, shows that per pupil spending has steadily risen in the past two years and now exceeds the previous high.

Several things baffle me:

1) Why are per pupil spending levels so low on this chart? I always thought per pupil spending now exceeded $20,000 in New York. But this chart has per pupil spending well under $9000.

2) If spending in New York City public education is recovering, why are class sizes still ballooning?

3) A secondary chart shows that per pupil spending has actually declined in 19 percent or more schools. If school funding is based upon enrollment, how can this happen? Shouldn’t per pupil spending have a base floor? And why do some schools have much larger per pupil spending gains than others? Could special needs students and extra grants explain that?

Related stories:

Per pupil spending by school district in the United States

An explanation of when $20,000 is not enough to teach a student.

Public-school spending dropped for the first time

Great English teachers improve students’ math scores

This article also appeared here.

Better English teachers not only boost a student’s reading and writing performance in the short term, but they also raise their students math and English achievement in future years. That’s according to a working paper, “Learning that Lasts: Unpacking Variation in Teachers’ Effects on Students’ Long-Term Knowledge,” by a team of Stanford University and University of Virginia researchers presented at the 7th Annual Calder Research Conference on January 23, 2014.

The researchers, Benjamin Master, Susanna Loeb and James Wyckoff, looked at 700,000 students in New York City in third through eighth grade over the course of eight school years (from 2003-04 to 2011-12). Their research initially confirmed the lasting impact of good English language arts or math teachers within their subjects. These teachers not only produce higher than expected test scores during the year that they are teaching the students, but their students go on to score better in that subject in subsequent years. Specifically, one-fifth of a teacher’s value added to achievement persists into the subsequent year.

More surprising were the crossover effects from English to math. The researchers found that the students of good English language arts teachers had higher than expected math scores in subsequent years. And this long-term boost to math performance was nearly as large (three quarters) as the long-term benefits within the subject of English. Conversely, good math teachers had only minimal long-term effects on English performance. Their positive effects were more subject specific.

“Our findings reinforce the value of investments in student learning in ELA (English language arts), even if the immediate effects of teachers or other instructional interventions may appear modest in comparison to effects on short-term math achievement,” the authors wrote. The authors added that their motivation for this study was a concern that many school districts are too narrowly focusing on rating teachers based on short-term test gains and they wanted to try to understand what kinds of teaching produce long-term learning benefits.

Why English teaching matters so much in other subjects is unclear. Some speculate that other subjects require some amount of reading and writing, whereas no math is required in many other classes. For example, you have to be able to read and understand word problems to do well in math.

The researchers also found substantial demographic differences in the long-term benefits to good teaching. More long-term benefits to good teaching were found in schools that serve more white and high income students. Long-term benefits to good teaching were smaller in schools dominated by minority and low-income students.

Data show students who race through a typing app learn less, but possibly more in a reading app

A big selling point for a lot of educational software is that it’s engaging like a video game. Students are motivated to progress from level to level and so they pay attention and work hard. Some kids, and this is particularly true with competitive boys, are so motivated that they race against each other to see who can hit a level first.

I first noticed this racing phenomenon in a so-called blended learning classroom in Los Altos, California back in 2011. They were using online worksheets produced by Khan Academy to learn math in fifth grade. During my classroom tour, I saw boys craning their necks to check out each others’ computer screens to see where their neighbors were. Some were on 10 and some were on 11. The boys were having a blast. But there was no time to click on a video and hear an explanation for something they didn’t understand well.

Even then Sal Khan, the website’s founder, was concerned that students weren’t retaining the math they were learning online in long term. Six months later, he said, a lot was forgotten. But it was unclear whether speed was a factor. Perhaps even the slow, methodical students weren’t retaining the material very long.

So I was fascinated when data scientists at Applied Predictive Technology (APT) specifically looked at speed when they analyzed the experience of 1200 students at D.C. Prep, a charter school network in Washington D.C., that was using two educational apps in the classroom this past fall. One was a reading program, Raz-Kids, for kindergarten through third grade. The other, Typing Club, is aimed at second through seventh grade. It turned out that speed is a complicated thing and, depending what you’re trying to learn, going fast might be beneficial. And other times, it’s detrimental.

First the data. 504 kids were on the Raz-Kids reading program this past fall where they earn stars (or points) and progress from level to level as they listen to, read and take quizzes on clusters books. Students used the app in the classroom and could access it at home if they wanted to. The app itself retains a lot of data on how much time kids spend on it, what order kids do the tasks, how many books each kid reads, etc. Children’s reading levels were assessed twice, at the beginning of the school year and again in December to seem how much each child progressed. The school also provided APT with children’s school records.

Researchers found that for first and second graders, the more kids used the reading app, the more their reading scores increased. First graders who read over 30 books were correlated with a 1.06 level increase in STEP scores. Second graders who read over 20 books were correlated with a 1.2 level increase in STEP scores. There was a much weaker correlation for kindergarten students . And the app didn’t make a difference at all for third graders. First graders who listened to as many books as possible, even if they skipped the quizzes that checked for comprehension, did the best. In other words, exposure to large quantities of words matters more than accuracy in first grade reading. However, by second grade, it mattered more to follow the listen, read, quiz steps in order.

Sarah Hinkfuss Zampardo, a principal at Applied Predictive Technologies, said that the app was most useful for kids with behavioral issues. The kids with the most behavioral actions on their student records saw a lot of improvement. But she also pointed out that these tended to be some of the weaker students in the class and “it’s easier to improve if you’re starting from a lower place.” Meanwhile, the strongest readers in the classroom tended to use the app more at home. “But Raz-Kids wasn’t necessarily making them stronger,” Zampardo clarified.

Meanwhile, in typing, quality mattered more than quantity. At DC Prep, 573 students used the Typing Club app. And like Raz-Kids, the app retains all sorts of data on usage. APT researchers found that boys and girls tended to use the app in two distinct styles. Some students, particularly boys, tried to advance through levels as quickly as possible. Others, particularly girls,, tried to achieve the highest score possible on a level before progressing.

APT data analysts found that students took the time to “fill in,” or go back and complete levels to achieve the highest score, advanced in reaching their words-per-minute goal more rapidly than students who would “fly through” the program, or get through each level as quickly as possible. The methodical students who went slower had a 36% improvement in typing. The “fly through” students had only a 17% improvement.

So is competitive “flying through” behavior good in reading, but not typing? “I don’t know if we know enough to say students are flying through in the same way. Maybe in Raz-Kids, the kids are more excited to read the next book,” said Zampardo, and not just seeking the bragging rights of the next level.

Crowdsourcing education data

Crowdsourcing was a big theme at the 2014 federal datapalooza conference devoted to education on January 15, 2014. Linked In’s Christina Allen pointed out that her company is sitting on a “large-scale data base of outcomes.” That’s because users report where the went to school and their employment history. If mined properly, the Linked In database could give high school students a sense of job prospects at different universities. Another start up, HowsMyOffer.com, asks students to voluntarily share their college financial aid offers (“the shopping sheet”). The idea is to demystify the financial aid process and shine a light on the inconsistent offers that colleges make. Yet another, Student Success Academy, is crowdsourcing high school counseling.

These ideas are brilliant, but I wonder about the veracity of self-reported data. We all know how often people lie about their education and job history. (I’d be curious to learn what the lie detection rate is at Linked In). Wouldn’t the outcomes database contain a giant amount of incorrect data?

Crowdsourcing is cheaper and easier than collecting verifiable data. It’s great for when you want people’s opinions. But I don’t think crowdsourcing is used very much in the medical field. Why does it make more sense for education?

Unlikely to graduate college if you take time off after high school

I’m always telling high school graduates to take time off after high school to do something interesting before college. That’s what I did. My parents feared I would never go to college. But I won out in the end. And the downtime — after the pressure cooker of high school — helped me figure out what I wanted to major in. But the latest data from the National Center for Education Statistics suggests that my parents were right to worry.

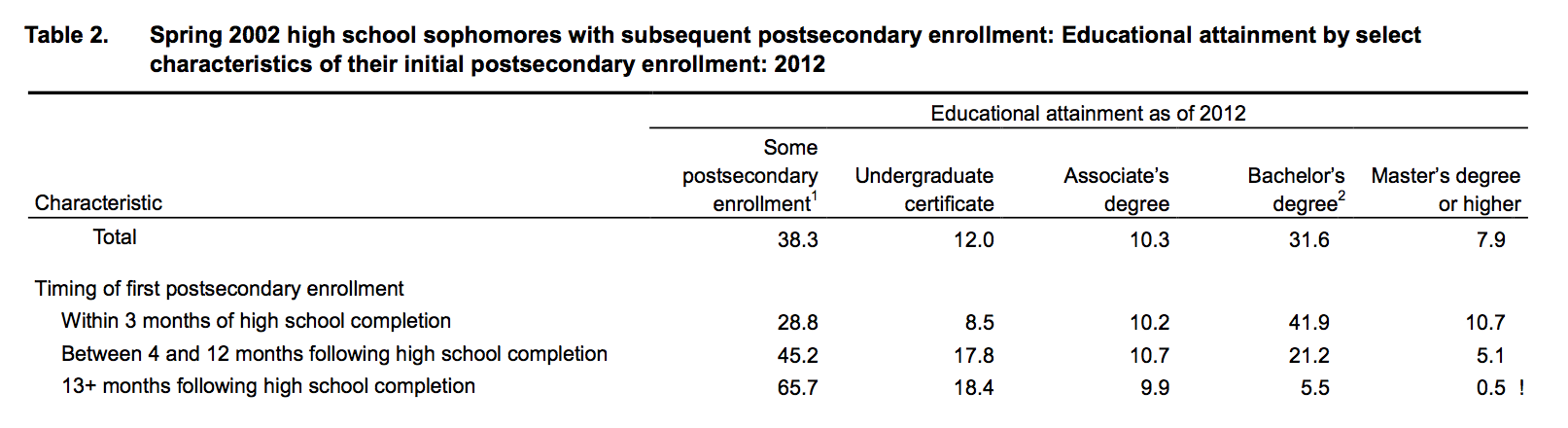

According to a longitudinal study that tracked students from their 10th grade year in 2002 through their mid-twenties in 2012, only 6 percent of students who took a year or more off after high school earned a bachelor’s degree by the time they were 25 to 26 years old. But 42 percent of students who went to college straight after high school completed their B.A. or B.S. degrees during that 10-year time period.

Source: NCES Education Longitudinal Study of 2002 (ELS:2002): A First Look at 2002 High School Sophomores 10 Years Later (Table 2)

I’m not quite ready to tell all kids to go straight to college. I’d like to see this data broken down by the selectivity of the college these students eventually go to. I would guess that the graduation rates of students who took off a year, but still go to a top college are fairly high.

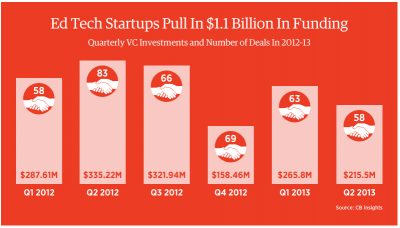

Is Ed Tech Investment Slipping?

The Forbes 30 under 30 confers celebrity status to a bunch of twentysomethings in more than a dozen fields — including education. Many of them are trying to get rich at the public trough by selling educational software and high-tech tools to schools. But what caught my eye was a tally of investment dollars going into start-up education technology companies.

If we were really in boom times, you’d expect that number to be going up. Instead, investor enthusiasm for high-tech education seems to be diminishing. Of course, you shouldn’t read too much into quarterly venture capital figures. One outsized deal can skew the numbers. But it will be interesting to check back again later this year.